Diabetic Retinopathy

By Dr. Peter Y. Chang, MD, FACS

Diabetes affects 415 million adults worldwide, and it is becoming more prevalent in children and adolescent thanks to the unhealthy diets and physical inactivity that have become the hallmarks of our modern society. Excessive hunger and thirst, frequent urination, weight loss, fatigue, and blurry vision are the classic early symptoms. However, it is estimated that in the U.S. 1 out of 3 patients remains undiagnosed, because these symptoms can be quite mild (that is especially true for type 2 diabetes). In addition to keeping up with routine physicals and blood work with your primary care doctor, getting a dilated fundus exam is critical in detecting early vascular changes of the eye. In fact, an astute observer can learn a lot about your overall health just by an eye exam!

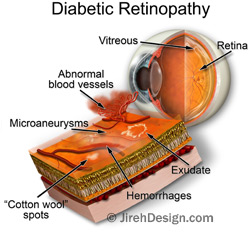

What is diabetic retinopathy? Simply put, chronically elevated blood sugar leads to pathological alterations in the small blood vessels supplying the retina, in turn causing potentially irreversible vision loss. It usually takes several years for the high sugar to cause noticeable changes on the retina, but it is recommended that every newly diagnosed diabetic patient gets a yearly eye exam to catch any early changes (in fact, that is a good practice for anyone). The retinopathy progresses in stages and can be broadly categorized into:

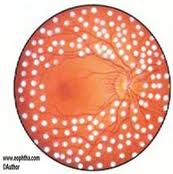

- Nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR): this can be mild, moderate, or severe, based on the amount of bleeding and vascular changes noted on the fundus exam. Patients do not usually have vision change unless there is associated macular edema (more details below), or if there is early cataract formation as a result of the elevated sugar. Some of the common findings your doctor might use to describe this stage of retinopathy include: microaneurysm, dot-blot hemorrhages, cotton wool spots, vascular attenuation, venous beading, and intraretinal microvascular abnormality (IRMA). Venous beading and IRMA are two of the defining features of severe NPDR. If present, the risk for progression to the proliferative stage of diabetic retinopathy is quite high. Regardless of the stage of NPDR, the standard of care is glucose, blood pressure, and cholesterol control. Laser or intraocular injection are typically not indicated during NPDR, unless there is concomitant diabetic macular edema. NPDR staging can regress nicely if diabetes is under good control and the patient’s overall health is good.

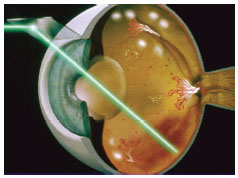

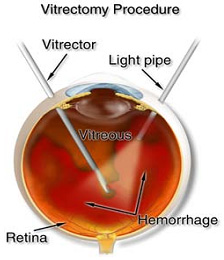

- Proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR): the retinopathy enters this stage when the retina is so deprived of oxygen that numerous chemical mediators are up-regulated inside the eye, ultimately leading to abnormal proliferation of blood vessels. This so-called neovascularization can grow anywhere on the retina, but most often on the surface of the optic nerve and along the retinal veins. These abnormal vessels are fragile, and thus can bleed into the vitreous gel. This vitreous hemorrhage can cause sudden loss of vision and can be quite frightening (and this is usually when a diabetic patient stops taking his vision for granted!). To prevent such an occurrence, your doctor will likely recommend in-office panretinal photocoagulation (“peripheral laser”) in order to help the neovascularization regress. If hemorrhage is significant and does not clear spontaneously, then the doctor will refer you to a vitreoretinal surgeon for vitrectomy, so that the blood can be physically removed (and laser can be done at the same time to help prevent future hemorrhage).

- Tractional retinal detachment (TRD): If laser is not done to suppress the neovascularization, with time, the abnormal proliferation of vessels, together with numerous other complex biochemical alterations that happen at the junction of vitreous gel and the retina, will lead to opacification and thickening of the vitreous. The abnormally strong vitreous can then begin to contract and, in the process, pull the retina away from the eye wall. This is referred to as TRD, to distinguish it from the types of retinal detachment caused by a retinal tear or other systemic conditions (I will write a separate blog on retinal detachment later). If TRD is close to the center of the eye and threatening central vision loss, then a vitreoretinal surgeon will perform a vitrectomy to remove the abnormal vitreous. In the ideal world, no diabetic patient should ever develop TRD because they would be so closely monitored that their retinopathy not allowed to get to this point. In reality, unfortunately, far too many patients suffer irreversible blindness because of it.

- Diabetic macular edema (DME): this refers to the swelling of the macula, which is the center of the retina that governs our central vision. The swelling is due to leaky, fragile vessels that form as a result of diabetes. DME can accompany either NPDR or PDR, so it should always be watched for. If you have NPDR and your central vision is gradually worsening, chance is that you have DME. In addition to the aforementioned control of glucose, blood pressure, and cholesterol, the treatment for DME includes intraocular injections of anti-VEGF and steroids, focal laser, and even vitrectomy for very difficult cases.

The bottom line: maintaining a good control of your diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia are of paramount importance when it comes to diabetic retinopathy prevention. However, if you already have retinopathy, it is never too late to seek out a vitreoretinal specialist in your area for a thorough dilated eye exam.

Dr. Chang is a vitreoretinal and uveitis specialist at MERSI. He is accepting new patients and has a strong interest in diabetic retinopathy among other retinal diseases.

#diabetes #diabeticretinopathy

Diabetic Retinopathy

Diabetes

Type 1, previously called juvenile-onset or insulin-dependent diabetes, is characterized by beta-cell destruction and usually leads to absolute insulin deficiency.

Type 1, previously called juvenile-onset or insulin-dependent diabetes, is characterized by beta-cell destruction and usually leads to absolute insulin deficiency.- Type 2, previously called adult-onset or noninsulin-dependent diabetes, is characterized by insulin resistance with an insulin secretory defect that leads to relative insulin deficiency

What is diabetic retinopathy?

Diabetic retinopathy is a disorder of the retina that eventually develops to some degree in nearly all patients with long-standing diabetes mellitus. While defects in neurosensory function have been demonstrated in patients with diabetes mellitus prior to the onset of vascular lesions, the earliest visible clinical manifestations of retinopathy include microaneurysms and hemorrhages. Vascular alterations can progress to retinal capillary nonperfusion, resulting in a clinical picture characterized by increased numbers of hemorrhages, venous abnormalities, and intraretinal microvascular abnormalities (IRMA).

A later stage includes closure of arterioles and venules and proliferation of new vessels on the disc, retina, iris, and filtration angle. Increased vasopermeability results in retinal thickening (edema) during the course of diabetic retinopathy.

Visual loss results mainly from macular edema, macular capillary nonperfusion, vitreous hemorrhage, and distortion or traction detachment of the retina.

Diabetes is the leading cause of new blindness among working age adults ages 20-74 years

What are the stages of diabetic retinopathy?

Diabetic retinopathy has four stages, mild nonproliferative retinopathy, moderate nonproliferative retinopathy, severe nonproliferative retinopathy, and proliferative retinopathy. These are determined based on fundus exam findings. There are times when you doctor at MERSI may need to perform fluorescein angiography or an OCT scan of the macula to further evaluate and classify your diabetic retinopathy.

How does diabetic retinopathy cause vision loss?

There are two main ways that elevated blood sugar in diabetes can lead to visual loss. Abnormal blood vessels can grow. Due to the fragile nature of these vessels they often leak and bleed causing blurriness and distortion of vision. Alternatively incompetent damaged blood vessels can leak into the macula, the part of the retina that is used for center vision.

This leads to macula swelling also referred to as macular edema.

Who is at risk for diabetic retinopathy?

All people with diabetes Type 1 or Type 2 are at risk to develop diabetic retinopathy.

Duration of diabetes is a major risk factor associated with the development of diabetic retinopathy.

After 5 years, approximately 25% of type 1 patients have retinopathy. After 10 years, almost 60% have retinopathy, and after 15 years, 80% have retinopathy.

Of type 2 patients who have a known duration of diabetes of less than 5 years, 40% of those patients taking insulin and 24% of those not taking insulin have retinopathy. These rates increase to 84% and 53%, respectively, when the duration of diabetes has been documented for up to 19 years. Proliferative diabetic retinopathy develops in 2% of type 2 patients who have diabetes for less than 5 years and in 25% of patients who have diabetes for 25 years or more. These percentages are based on data from the 1980s before there was closer monitoring and tighter glycemic control, and they may have improved(Data from Preferred Practice Patterns AAO).

Does diabetic retinopathy have any symptoms?

Often the disease is asymptomatic. Blurred and obscured vision may occur from macular edema or from bleeding inside your eye.

What are the symptoms of proliferative retinopathy if bleeding occurs?

At first, you might see a few specks of blood, or floaters in your vision. If this occurs please see your doctor at MERSI as soon as possible. As you may benefit from treatment before more serious bleeding occurs.

Sometimes the bleeding will stop on its own. However if proliferative diabetic retinopathy is left untreated it can lead to severe vision loss and even blindness.

How are diabetic retinopathy and macular edema detected?

Diabetic retinopathy and macular edema are screened for at your annual comprehensive eye exam. The physicians at MERSI can examine your retina for the earliest signs of disease, including; the presence of leaky or abnormal blood vessels, the presence of retinal exudate or areas of retinal ischemia, as well as any damage to the nerve tissues of the retina. If there is suspicion of diabetic retinopathy your doctor may recommend getting a fluorescein angiogram(FA) and an OCT scan. These tests are used to detect leakage from blood vessels and early accumulation of intra-retinal or sub-retinal fluid.

How is diabetic retinopathy treated?

During the first three stages of diabetic retinopathy, usually no treatment is needed, unless you have macular edema. To prevent the development or progression of diabetic retinopathy, people with diabetes should optimize their blood sugar, blood pressure, and cholesterol levels. Proliferative retinopathy is treated with panretinal photocoagulation(PRP) or scatter laser therapy. Panretinal photocoagulation works by shrinking abnormal blood vessels. However if the bleeding is severe, you may need to undergo retinal surgery to remove the blood in your eye. It is important to keep in mind that with laser therapy and appropriate follow-up the risk of blindness can be reduced However, treatment for diabetic retinopathy often can’t restore vision that has already been lost. That is why prevention is key and appropriate follow up with your doctor is crucial.

How is a macular edema treated?

Recent studies have shown that Macular Edema is best treated with intra-ocular injections of anti-VEGF therapy and or concomitant focal laser therapy or a combination of both. This protocol decreases

the amount of fluid in the retina. It is important to understand that focal laser therapy stabilizes vision and reduces the risk of vision loss by about 50 percent.

What is a Pars Plana Vitrectomy?

If you have a lot of blood that accumulates and does not clear from the vitreous gel, the center of your eye your doctor may recommend surgery: pars plana vitrectomy(PPV) to remove the blood and restore your vision.

During a pars plana vitrectomy a small instrument is used to remove the vitreous gel and blood that is obscuring your vision. As the vitreous is removed it is replaced with a balanced salt solution. A pars plana vitrectomy is typically performed in an outpatient setting with the patient going home after the surgery with there eye patched.

What can I do to protect my vision?

The most important thing you can do is obtain an annual comprehensive eye exam with a Retinal specialist. Screening exams are crucial in patients with Diabetes as often the disease can be asymptomatic despite the presence of retinal damage.

It is also important to:

- Maintain a healthy lifestyle with exercise and weight control

- Optimize blood sugar control, blood pressure, cholesterol levels

- Monitor renal status

- Optimize HgbA1c: glycosylated hemoglobin, is a form of hemoglobin that is measured primarily to identify the average plasma glucose concentration. The HbA1c level is proportional to average blood glucose concentration over the previous four weeks to three months.

A pivotal study, Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT), looked at thousands of patients with diabetes showed that better control of blood sugar levels delayed the development and slowed the progression of diabetic retinopathy. Other studies also showed that controlling ones blood pressure and cholesterol can reduce the risk of vision loss.

We continue to learn the role of the pivotal players in Diabetes/Diabetic Retinopathy/Diabetic Macular Edema via new clinical advances/clinical trials and thus continue to evolve with innovative strategies to add new modalities to our treatment paradigm and strive for a cure to this vision impairing disease.

If you or a family member has diabetes please make an appointment to see us at MERSI, so that we can optimize your vision; where we share a global concern for the united goal of preservation of vision and elimination of diabetic retinopathy and its complications and strive to eliminate it as a cause of blindness.

To print this article, click here.

For more on diabetic retinopathy:

MAKE AN APPOINTMENT

Our Physicians

All of our physicians have completed Fellowships in their specialty.

C. Stephen Foster, MD, FACS, FACR

Founder

Stephen D. Anesi, MD, FACS

Partner and Co-President

Peter Y. Chang, MD, FACS

Partner and Co-President

Peter L. Lou, MD

Associate