Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis and Associated Uveitis

by Stephen D. Anesi, MD, FACS

July is juvenile arthritis awareness month, and thus I feel it is time to reconnect with those who are aware of and fight for children with the most common presentation of this disease, or educate those who are hearing about this for the first time… Juvenile idiopathic arthritis, or JIA, is a multisystemic autoimmune disease which represents the most common form of arthritis of childhood. It affects approximately 70,000 children in the United States and is also the most common identifiable systemic association with pediatric uveitis. Different types of JIA exist, and of those defined by the International League of Associations for Rheumatology (ILAR) classification system in 2004, the most common subtype of JIA to present with uveitis is the oligoarticular type, meaning those children with fewer joints afflicted by inflammation.

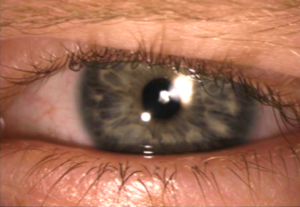

Up to 12% of children with JIA may present with uveitis, and, most disturbingly, this inflammatory condition is almost entirely asymptomatic. These children simply do not normally suffer from the common complaints of redness, burning, pain, blurring, floaters, and light sensitivity that most uveitis patients describe. Rather they go on through life as happy as ever, blissfully unaware of the smoldering inflammation that rages on within their two precious eyes, often from a very young age when they are unable to communicate or even discern what abnormal vision is at all. Just as the child shown below (seen just this week!), these patients will often present to their eye doctor with a completely normal appearing eye from a gross perspective. However, the slit-lamp microscope will be able to see the inflammatory blood cells swirling in the front of the eye, as well as any subtle formation of cataract or corneal pathology, and begin to recognize that this child will need aggressive anti-inflammatory therapy. In addition, it is a well-recognized fact that the activity of joint and eye inflammation is not always concordant, making it even more difficult to detect ocular inflammation, especially if the child is not examined regularly. It is for these reasons that the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) in 2006 published recommendations for screening children with JIA for uveitis, which included monitoring children with ANA positive oligo- or polyarthritis JIA presenting prior to age 7 every 3 months, and all other JIA children every 6 to 12 months.

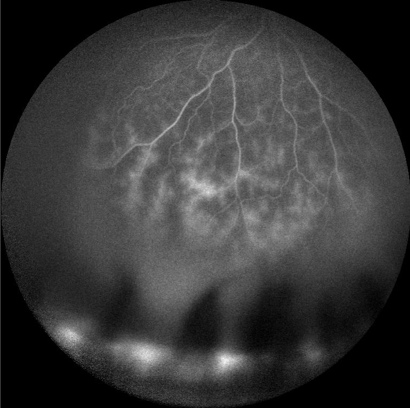

There are other risk factors for development of uveitis in JIA children which include younger age of onset of arthritis (2 to 5 years old), female sex, as well as certain genetic markers. Much research has been dedicated to finding other factors that may be able to alert multi-disciplinary providers who care for these children of the level of risk for development of uveitis, however most of these markers are still not routinely available in a clinical setting or have merely been proposed without sufficient vetting by other researchers. Sadly, these children are often discovered to already have been affected by structural complications of the eye due to their chronic inflammation by the time they are first diagnosed, especially in children with more active inflammation, ANA positivity, and shorter time period between diagnosis of arthritis and uveitis (including those who are diagnosed simultaneously). Some of these complications include cataract, glaucoma, band keratopathy (a collection of calcium just under the surface of the cornea that can cause blinding and great discomfort), scarring of the iris to the underlying lens called posterior synechiae, or retinal changes resulting from hypotony (low eye pressure) or macular edema (swelling in the central retina responsible for good vision). Shown below is an example of retinal vasculitis, a particularly severe and likely underappreciated feature in some children with JIA uveitis – this picture was taken from a teenage girl who has suffered with uveitis since age 3. In one study of JIA children, 24% of them, upon finally presenting to the uveitis specialist, had legally blind vision (20/200 or worse) in the better seeing eye… a complete and utter tragedy, and potentially avoidable.

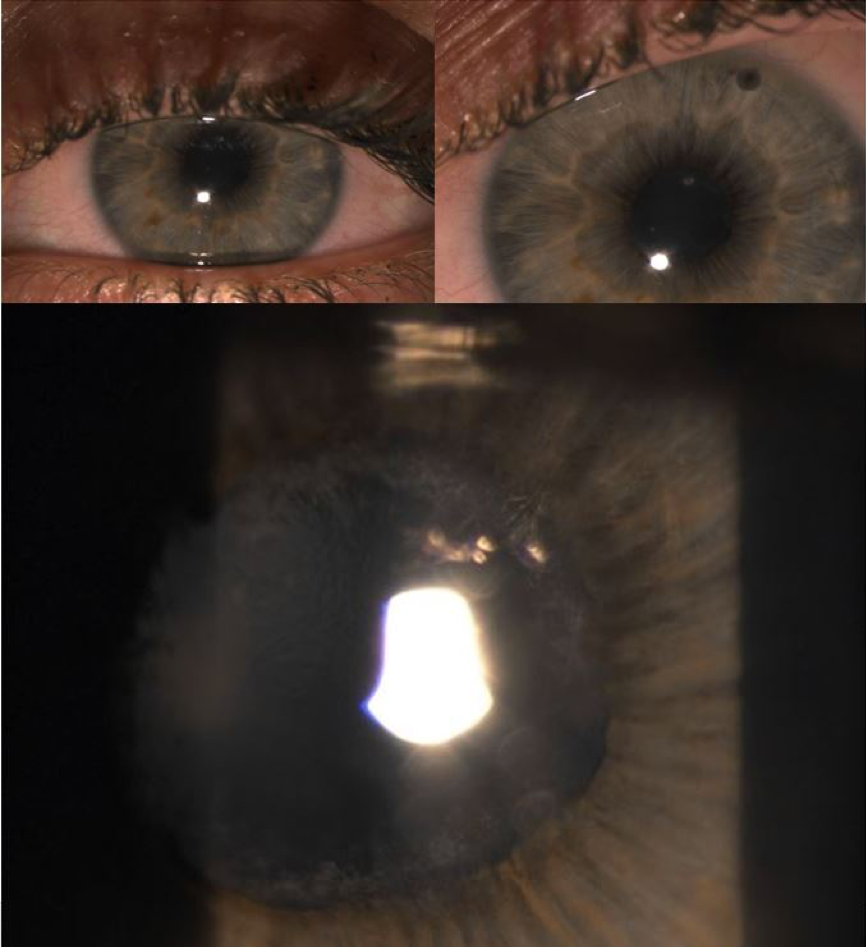

Not to be forgotten in this incredibly difficult situation are the children with JIA and associated uveitis that then become adults and, unimaginably at times, become lost in the system or have a hard time transitioning care between pediatric and adult doctors to help them continue to control their blinding chronic inflammatory disease. If one was to read the literature on this subject, one would certainly come across several reports attempting to declare that these patients are overwhelmingly doing much better in more recent times with better medications and better screening, however I, and most of my close colleagues, would strongly disagree with this bold yet erroneous statement. A closer look at the literature would also reveal several reports where these patients still present with poor outcomes despite attempts by us and others to increase awareness of JIA uveitis and the need for more aggressive diagnosis and management. One study looking at outcomes in JIA children into adulthood showed that 40% of these children had vision impairment, 20% had poor vision, and vision was “totally lost” in 10%, with 100% of patients presenting with at least one ocular complication. Our group at MERSI has published a large case series of 77 adult patients with JIA uveitis, and found that 72% of them had at least one eye complication and over 50% had ongoing inflammation. This young woman in her 20s shown below, with an eye that at first glance looks relatively normal, just recently required an emergent laser procedure and later cataract surgery to help fight severe acute glaucoma. Clearly this is not a disease that just “burns out” nor is it by any means doing well.

In addressing therapeutic options with patients and their families, the approach is not too unlike that of adult versions of this disease – aggressive yet appropriate immunosuppressive therapy aimed at the vanquishing of all inflammation without reliance on ANY steroid drops or pills. This last point is extremely important – note steroids are not tolerated at all, and that so called “low dose” steroid maintenance, as still regularly employed by some willfully ignorant or demonstrably incapable providers, is also not a viable option. The new standard of care for these children should be steroid-sparing therapy with a recipe of medications designed to oppose the harmful actions of the overactive immune system, whether they include chemotherapy-style or biologic medications, or both. Studies have also shown that JIA uveitis patients will present with less complications in the eye when they have been appropriately treated with these “aggressive” medications, which are quite safe in the hands of experienced providers, rather than with steroids. A major milestone in the treatment of children with uveitis in the U.S. recently occurred with the FDA approval of Humira® as the first and only (thus far) approved treatment for pediatric uveitis, which occurred because of efforts made to study the positive effects of this medication in children with JIA uveitis. This is an encouraging step in the right direction, however many more need to be taken before we as uveitis specialists may begin to realize a true paradigm shift in the treatment of these children.

Much more work is left to be done to help these children in the future, but truly the most important thing that one and all may do to help them is to increase awareness of and screening for this blinding disease, as well as the need to abandon the folly of steroid dependence and embrace the early and appropriate use of steroid-sparing therapy. It is only with increased awareness and appreciation for the severity of this condition that we will actually have the chance to realize better outcomes for these patients… our children… so they may go on to see the world in all its brilliance for years to come.

Our Physicians

All of our physicians have completed Fellowships in their specialty.

C. Stephen Foster, MD, FACS, FACR

Founder

Stephen D. Anesi, MD, FACS

Partner and Co-President

Peter Y. Chang, MD, FACS

Partner and Co-President

Peter L. Lou, MD

Associate